Bod Pod Consumer Scale Comparison Tests: Part III (The In Depth Statistical Analysis)

(Note from Ray: Two weeks ago when I published the results of the Bod Pod and body fat scale testing, a reader who happens to be a PhD Candidate in Pharmaceutical Sciences – Nathaniel Page – made an offer to do a guest post with a bit of analysis on the results from a statistics standpoint. In particular, to explain why it is that from a pure numbers standpoint these companys can often claim such high levels of accuracy, when the real person to person results we saw were much different. Some of the below may be hardcore geek, but if you read through the text – it really explains why we see such differences. Thanks Nathaniel – awesome stuff!)

Being a science nerd and avid runner, I looked at the pile of data Ray collected using the BF% scales and Bod Pod and felt an unhealthy overwhelming urge to analyze it. I volunteered my interpretation, Ray accepted and here is my guest post.

How Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA) Scales Work

Ray covered how the Bod Pod worked so I’ll cover some background about how bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) scales determine BF%. At the heart of the matter is that fat conducts electricity more poorly than lean body mass (muscle, bone, blood, etc) and the scales exploit this. When you stand on the metal pads, the scale shoots a small electrical current up one leg and down the other and measures the resistance (impedance) using Ohm’s Law. A person with more body fat will have a higher resistance than a lean person. Of course, the scale also measures your weight.

The scales then use a multiple regression equation to determine BF %. To develop the regression equation, the engineers that made the scale collect a whole bunch of descriptors of a population of people they want the scale to work for. These may include impedance, weight, height, sex, age, athletic status (or anything else). They also get a gold standard measure of BF%. They then use the descriptors to create an equation that will predict BF%. It is a balance between a using too few descriptors and having a poor equation and using too many and making a convoluted equation.

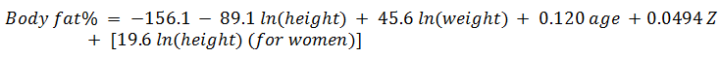

An example of one of these equations a scale may use is:

(Z is impedance (electrical resistance) in ohms, height is in meters, weight is in kilograms and age is in years (from reference Jebb et. al. Br J Nutr. 2000 Feb;83(2):115-22))

So to use this equation, the person will input their height, sex, age, and weight. The scale will determine impedance and weight, do the required math and spit out your BF%. Every scale/manufacturer will have their own special equations.

The problems with BIA scales is that the equation is the best fit for a given population of people. But you may not fit in that defined population and thus the equation may not accurately define you. That’s why some scales have a “normal” and “athlete” setting. The manufacturers have recognized that these two populations of people need different equations to describe them and the scales can switch between them. The other issue is that impedance can be altered by hydration status, calluses on their feet or a slew of other trivial factors.

A Brief Overview of Statistics

This section is for some of the readers who may not have a statistics background. For all the people well versed in the subject, I apologize in advance for the butchering of definitions and any other transgressions. When someone says that the two averages are statistically significantly different it means that the difference that is seen is not likely due to random chance alone. We usually use a cut off of less than 5% probability the difference is due to random chance and it is usually written as “p”.

A theoretical example; if I took 20 people and measured their heart rates before and after doing jumping jacks for 1 minute. The average HR before is 50 and after is 150 and I get p

Analysis of Scales

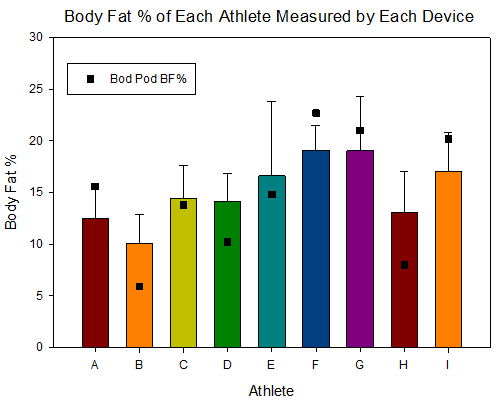

I had a nice pile of data to look at using the raw Excel files Ray posted. Using nine athletes (ATH) with measurements from 8 devices (the Bod Pod and 8 different scales/settings) I plotted the data two ways. The first graph is the mean ± standard deviation of athlete using the different devices. The Bod Pod BF% reading is the square for your reference. We see that some athletes have little variability in the BF% reading when using the different devices (ATH A, B and F) while others have a big spread (mainly ATH E). This goes back to the equations used by the scales and ATH E may not be as accurately described by them as the other subjects. The Bod Pod reading is right on top or very near the mean for most of the subjects but misses for a couple (ATH B and H)

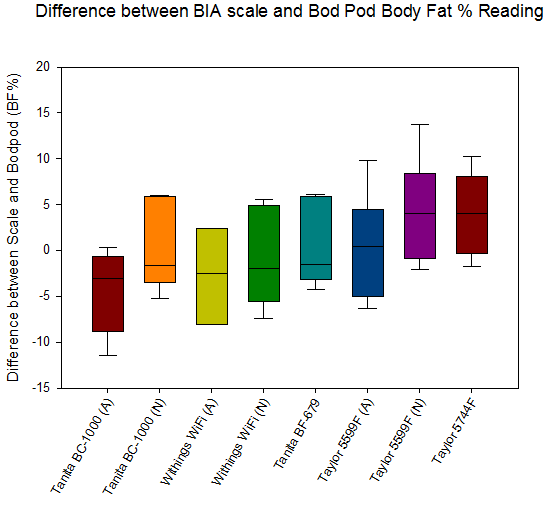

The second graph is the difference between the Bod Pod measurement and the BIA scales. If a scale gave the exact reading as the Bod Pod, the difference would be zero, if the scale gave a higher reading it would be positive and the opposite if the reading was less. The mid-line of the box is the median with the edges of the box being the 25th and 75th percentile. The whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles of the readings. Here we see some interesting trends. Most of the scales are centered around zero and some have a smaller spread than others but overall they look pretty similar. The Taylor 9955F seems to be a little more variable than the rest. If we look at the 3 scales operating in “athlete” or “normal”, the Tanita and Taylor model give higher readings in normal mode while the Withings scale looks like the readings are the same in either setting. Also, as Ray noted, the normal mode gave readings more in line with the Bod Pod.

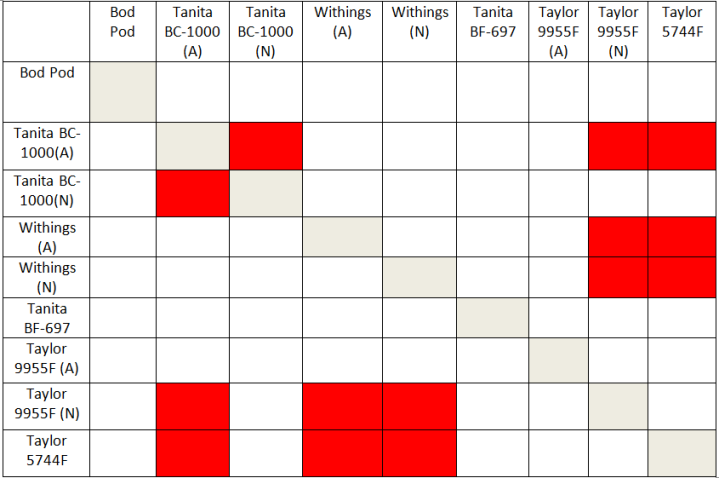

To have a more thorough understanding of the data I applied a Repeated Measure 1-Way ANOVA test with Tukey’s Post-hoc to tell me if any of the devices are significantly different from each other. The results are interesting but not how you’d expect. The full statistical results can be found here. The results are summarized in the table below. A red box indicates that the two devices are significantly different (p<0.05).

It looks like the measurements given by any of the scales are not different than the Bod Pod readings. The Tanita BC-1000 in athlete mode is trending but did not reach the 5% threshold (p=0.08). The Taylor 9955 in normal mode was also approaching significant (p=0.09) but trending higher than the Bod Pod. Interestingly, the difference between the athlete and normal mode was not significant for the Withings or Taylor scales suggesting it doesn’t matter which mode you use. The Tanita did give significantly different readings based on the mode with athlete mode giving lower readings. Again note that the term significant or different here is from a statistics terminology standpoint, and not a clinical (real life) standpoint.

Conclusions

All the scales tested give BF% measurements that is not statistically different than what the Bod Pod will spit out based on the population Ray used (self defined athletes who podium occasionally). Also it appears that athlete mode may not be necessary in the scales which have it (only the Tanita gave readings which were different between the two settings). Some people may get vastly different readings (athlete E) on different devices but on a whole the 9 devices are surprising similar.

Of course, these data say nothing about the absolute accuracy of the BIA scales or the Bod Pod, they are merely comparing the different devices. If we wanted to say something about the accuracy of the devices, we’d need to be comparing them to the gold standard measurement technique (DEXA) and we don’t have that data at this time. BIA scales and Bod Pod typically have an accepted accuracy of 3 BF% or so and we need to remember that. It could be theoretically possible that the scales are hitting the absolute BF% right on and the Bod Pod is the device that is missing the target. Looking at the first graph, it looks like for ATH B and H, the Bod Pod reading is quite a bit from the mean of all the devices. These two subjects may be poorly defined by the Bod Pod for some reason (maybe they have giant afros which mess with the air displacement) and BIA does a better job, we just don’t know.

While we don’t know about the accuracy, the BIA scales are overwhelmingly precise from my and others’ experience. If you measure the same way every day (i.e. methodology including hydration), the readings day to day will be consistent, allowing you to follow trends in the data to see how your BF and lean mass are changing over time. For those unsure about the difference between Accuracy and Precision you can read up here.

After seeing the data and analyzing it, I’m confident that the scales are a reasonable alternative to more expensive testing like the Bod Pod if you want an idea of your BF%. Because the absolute error of BIA and Bod Pod is similar, you’d be best off splurging and going to a more accurate testing method (DEXA) if you want pinpoint BF%. To me, it’s just not worth it of all the reasons Ray covered in the summary Part II.

Disclaimer:

I’m not a statistician; just a biomedical research student and pharmacist so while I think the analysis is valid/correct don’t hold me to it. Feel free to criticize my interpretation or present a different viewpoint, I’ll try not to take it too personally. Other than using a BIA scale, I also have no vested interest (financial or otherwise) in the performance of any of the devices tested.